2008 —

Catterline in Focus

Catterline in Focus

Scottish Art News, Issue 10︎

︎PDF

![]()

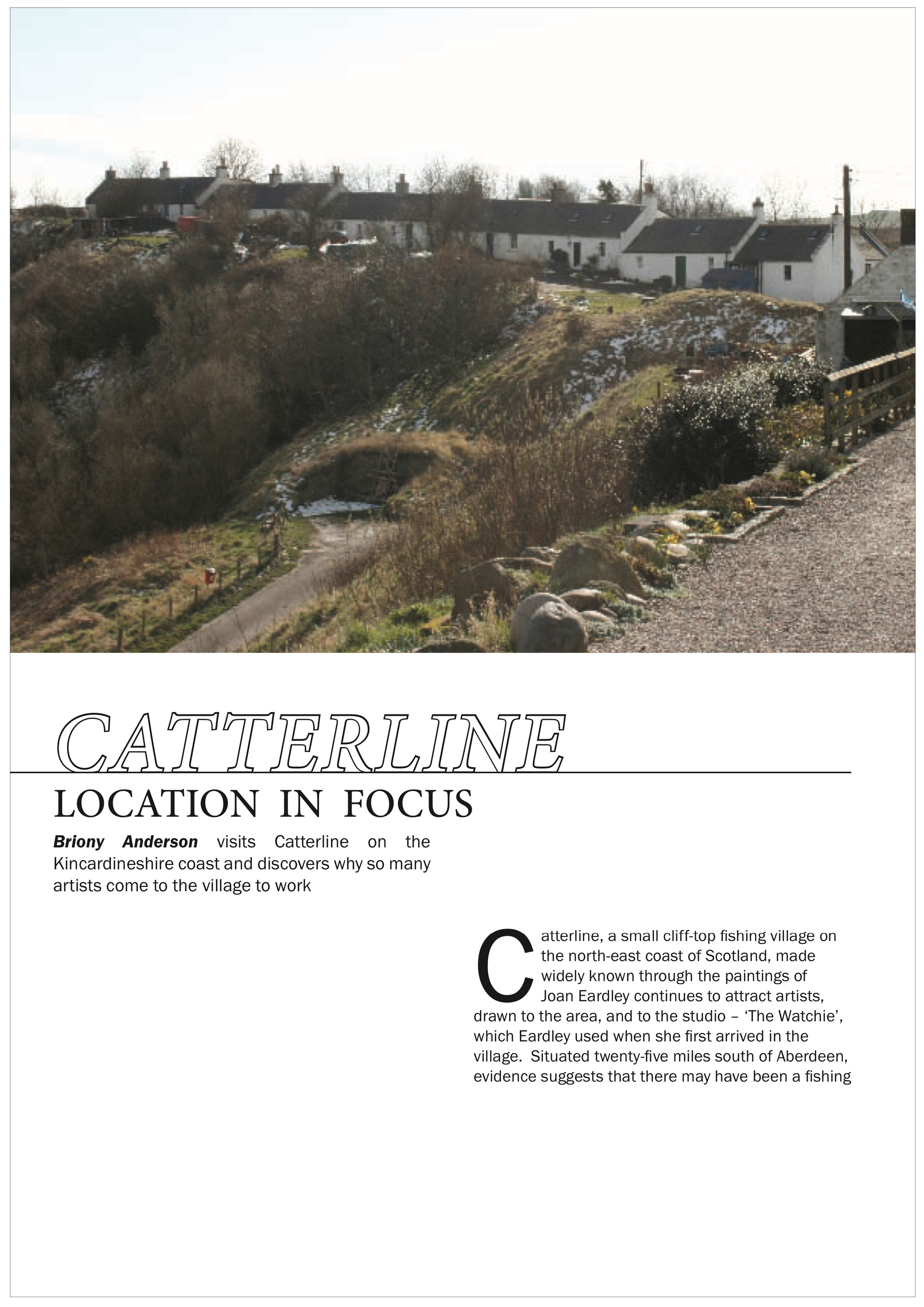

Catterline, a small cliff-top fishing village on the north-east coast of Scotland, made widely known through the paintings of Joan Eardley continues to attract artists, drawn to the area, and to the studio – ‘The Watchie’, which Eardley used when she first arrived in the village. Situated twenty-five miles south of Aberdeen, evidence suggests that there may have been a fishing community established in Catterline as early as the fourteenth century. Around 1835 the pier was built, a coastguard’s station established, and locally, the fishing industry thrived until the turn of the century when it reached its peak, before witnessing a steady decline during the course of the twentieth century.

Joan Eardley at Catterline

Eardley’s discovery of Catterline came in 1951, and this stretch of coast quickly joined inner city Glasgow as the impetus behind her work. It was during an exhibition of Eardley’s work in Aberdeen that friend and artist, Annette Stephen, had taken Eardley to visit Catterline where they came across the ‘The Watchie’ – the coastguard’s watch house, positioned at the highest point in the village and up for sale. It was subsequently bought by Stephen, made weather-tight for use as a studio and available for Eardley to work in. She painted there until she purchased Number 1 The Row as a studio and living space, often painting directly from her front door, looking out over the sea and down to the bay and harbour below. From this point, the seascape, surrounding landscape and its changing seasons were to feature as prominently in her life and work as the tenements and children of Glasgow – her time now divided between these changing urban and rural communities.

Visiting Catterline, it becomes apparent why the place made such an impact on Eardley – the rows of small, quaint, white-washed fishermen’s cottages juxtaposed against the endless northern sea and skies, echo the undulating line of the cliff edge – ‘it’s just a vast waste, vast seas, vast areas of cliff’, Eardley remarked in an interview. She also described the way in which she approached her Catterline paintings, often painting the same scene over and over as if each time, to develop upon the last, believing the more familiarity she had with the subject – the continual changefulness of the landscape – the more she could see in it to translate into her work. In 1959 she purchased Number 18, Catterline, again often painting directly from this spot. For example, Catterline in Winter (c.1963) was painted from this viewpoint. Interestingly, as time progressed, she seemed to move closer to the sea to paint, favouring the direct experience of being near the water to the distant vantage point of the cottages on the cliff, and a photograph taken by Audrey Walker shows Eardley sketching, perched on her shooting stick, in the sea itself. Unlike her Glasgow paintings, the community in Catterline does not feature in a figurative sense, but there is often some form of reference to it – a hint of human presence – whether in the drying salmon nets, fishing boats, washing lines, haystacks, beehives or in the smoke rising from the chimneys – the life of the inhabitants reflected in her paintings. Here, too, as in Glasgow, she was depicting a way of life that was disappearing. By this time, Catterline’s fishing fleet had virtually gone.

The artists Angus Neil and Lil Neilson who were close friends of Eardley’s also spent considerable time in Catterline, proving influential in the development of one another’s practice. Neilson actually came to live and work in the village, bequeathing The Watchie (which had been left to her), to friend and neighbour in the village, Ann Steed, with the request that the proceeds from sales of her paintings should be spent renovating it and making it available for artists to use once again.

The Watchie

Since the renovation was completed in 2003, it has continued to be used as it was when it first began life as an artist’s studio, providing a work (and living) space for artists. With its large windows looking out over the expanse of the North Sea, it has seen a number of artists make use of its studio space over the last five years. Artists have spent anything from a weekend to several months in The Watchie, having requested the time for self-directed practice rather than having been selected through an open submission process as is the common procedure for residency programmes. Artists Joanne Tatham & Tom O’Sullivan exhibited work in The Watchie in 2003, and as its use is not restricted to the visual arts, writer Judith Findlay has also used the space to work. For the last two years, artist Anna King has spent the winter months working in The Watchie and towards the end of 2007, Norwegian artist Ingeborg Kvame undertook a residency as part of the North Sea project, an exchange programme between Scotland and Norway organised by the Scottish Society of Artists and Stavanger 2008. During her residency, she made drawings directly influenced by the area and by Eardley and Neilson and the time they spent in Catterline together. The work produced during the residency was shown in Edinburgh and there are further plans to exhibit in Catterline in the summer of 2008.

Catterline Arts Festival 2003/05

When The Watchie was ready for use, the idea arose to organise a local arts festival and a number of local, national and international artists were invited to exhibit work throughout the village, utilising all of its spaces including ‘The Creel Inn’, the homes of local residents and St Philip’s church where artists Dalziel + Scullion exhibited their three part film Water Falls Down (2001). An exhibition of the work of Lil Neilson was held in The Watchie. The festival was initiated and organised by five members of the community, all working within the arts, including Ann Steed (Assistant Keeper of Fine Art at Aberdeen Art Gallery) and Iain Irving (MA course leader at Gray’s School of Art) who wanted to celebrate contemporary visual art in Scotland while also acknowledging the village’s visual arts heritage. Artists were keen for their work to be seen in this new context, and artist David Blyth responded to Catterline itself through an exploration of local myth in his work. The festival took place again two years later, this time with more of an emphasis on Catterline, a number of artists making work directly in response to its context. Through the success of the first festival, more spaces were made available by local residents to exhibit in and The Creel Inn has since hosted a regular programme of exhibitions. The artistic significance, connections and undeniable sense of community spirit in Catterline is perhaps summed up in this festival.

Artists in Catterline

When I visited Catterline at the end of March, The Watchie was being used by local artist Mike Samson, busy preparing paintings for an exhibition in Aberdeen, and by members of a community arts group. Artist Stuart Buchanan who re-located from Glasgow to Catterline and to Eardley’s house at Number 18 two years ago has just begun a one year residency in The Watchie. Although not directly influenced by Eardley, it seems that a knowledge of her work and her evocation of these surroundings will impact on his painting. Certainly, it is difficult to avoid visualising her paintings while looking at this landscape, demonstrative perhaps, of her direct and experiential approach to her work. This approach – her constant observation and subsequent interpretation of the austerity and drama of the landscape, the muted colours of the north-east in her paintings is documented in photographs of Eardley with her easel set up on the shoreline.

For artists who come and work in The Watchie, many will find it is more than a space, a studio – with its outlook and position, it seems to both encompass and be integral to the surrounding landscape. For Eardley, to be part of this landscape and to be directly responding to it was fundamental to her work. This intimate involvement within the landscape produces the intensity and immediacy conveyed through her paintings, as if she was reducing as much as she could, the physical and emotional distance between artist and subject. Immersed in the elements she was recording, the paint itself is indicative of this engagement, both in the energy of the brushstrokes and for example, by the incorporation of sand and grasses in the paint.

Her painterly response and involvement in the community at Catterline have left lasting impressions which are not likely to diminish but to continue to feed imaginations and creative minds for many years to follow. Throughout Scotland in 2008, a touring exhibition Impressions of Catterline 08 will take place. Opening at Montrose Museum, it features work by eighteen artists, each responding to Catterline and its surroundings.

Text copyright, Scottish Art News 2008.

Catterline, a small cliff-top fishing village on the north-east coast of Scotland, made widely known through the paintings of Joan Eardley continues to attract artists, drawn to the area, and to the studio – ‘The Watchie’, which Eardley used when she first arrived in the village. Situated twenty-five miles south of Aberdeen, evidence suggests that there may have been a fishing community established in Catterline as early as the fourteenth century. Around 1835 the pier was built, a coastguard’s station established, and locally, the fishing industry thrived until the turn of the century when it reached its peak, before witnessing a steady decline during the course of the twentieth century.

Joan Eardley at Catterline

Eardley’s discovery of Catterline came in 1951, and this stretch of coast quickly joined inner city Glasgow as the impetus behind her work. It was during an exhibition of Eardley’s work in Aberdeen that friend and artist, Annette Stephen, had taken Eardley to visit Catterline where they came across the ‘The Watchie’ – the coastguard’s watch house, positioned at the highest point in the village and up for sale. It was subsequently bought by Stephen, made weather-tight for use as a studio and available for Eardley to work in. She painted there until she purchased Number 1 The Row as a studio and living space, often painting directly from her front door, looking out over the sea and down to the bay and harbour below. From this point, the seascape, surrounding landscape and its changing seasons were to feature as prominently in her life and work as the tenements and children of Glasgow – her time now divided between these changing urban and rural communities.

Visiting Catterline, it becomes apparent why the place made such an impact on Eardley – the rows of small, quaint, white-washed fishermen’s cottages juxtaposed against the endless northern sea and skies, echo the undulating line of the cliff edge – ‘it’s just a vast waste, vast seas, vast areas of cliff’, Eardley remarked in an interview. She also described the way in which she approached her Catterline paintings, often painting the same scene over and over as if each time, to develop upon the last, believing the more familiarity she had with the subject – the continual changefulness of the landscape – the more she could see in it to translate into her work. In 1959 she purchased Number 18, Catterline, again often painting directly from this spot. For example, Catterline in Winter (c.1963) was painted from this viewpoint. Interestingly, as time progressed, she seemed to move closer to the sea to paint, favouring the direct experience of being near the water to the distant vantage point of the cottages on the cliff, and a photograph taken by Audrey Walker shows Eardley sketching, perched on her shooting stick, in the sea itself. Unlike her Glasgow paintings, the community in Catterline does not feature in a figurative sense, but there is often some form of reference to it – a hint of human presence – whether in the drying salmon nets, fishing boats, washing lines, haystacks, beehives or in the smoke rising from the chimneys – the life of the inhabitants reflected in her paintings. Here, too, as in Glasgow, she was depicting a way of life that was disappearing. By this time, Catterline’s fishing fleet had virtually gone.

The artists Angus Neil and Lil Neilson who were close friends of Eardley’s also spent considerable time in Catterline, proving influential in the development of one another’s practice. Neilson actually came to live and work in the village, bequeathing The Watchie (which had been left to her), to friend and neighbour in the village, Ann Steed, with the request that the proceeds from sales of her paintings should be spent renovating it and making it available for artists to use once again.

The Watchie

Since the renovation was completed in 2003, it has continued to be used as it was when it first began life as an artist’s studio, providing a work (and living) space for artists. With its large windows looking out over the expanse of the North Sea, it has seen a number of artists make use of its studio space over the last five years. Artists have spent anything from a weekend to several months in The Watchie, having requested the time for self-directed practice rather than having been selected through an open submission process as is the common procedure for residency programmes. Artists Joanne Tatham & Tom O’Sullivan exhibited work in The Watchie in 2003, and as its use is not restricted to the visual arts, writer Judith Findlay has also used the space to work. For the last two years, artist Anna King has spent the winter months working in The Watchie and towards the end of 2007, Norwegian artist Ingeborg Kvame undertook a residency as part of the North Sea project, an exchange programme between Scotland and Norway organised by the Scottish Society of Artists and Stavanger 2008. During her residency, she made drawings directly influenced by the area and by Eardley and Neilson and the time they spent in Catterline together. The work produced during the residency was shown in Edinburgh and there are further plans to exhibit in Catterline in the summer of 2008.

Catterline Arts Festival 2003/05

When The Watchie was ready for use, the idea arose to organise a local arts festival and a number of local, national and international artists were invited to exhibit work throughout the village, utilising all of its spaces including ‘The Creel Inn’, the homes of local residents and St Philip’s church where artists Dalziel + Scullion exhibited their three part film Water Falls Down (2001). An exhibition of the work of Lil Neilson was held in The Watchie. The festival was initiated and organised by five members of the community, all working within the arts, including Ann Steed (Assistant Keeper of Fine Art at Aberdeen Art Gallery) and Iain Irving (MA course leader at Gray’s School of Art) who wanted to celebrate contemporary visual art in Scotland while also acknowledging the village’s visual arts heritage. Artists were keen for their work to be seen in this new context, and artist David Blyth responded to Catterline itself through an exploration of local myth in his work. The festival took place again two years later, this time with more of an emphasis on Catterline, a number of artists making work directly in response to its context. Through the success of the first festival, more spaces were made available by local residents to exhibit in and The Creel Inn has since hosted a regular programme of exhibitions. The artistic significance, connections and undeniable sense of community spirit in Catterline is perhaps summed up in this festival.

Artists in Catterline

When I visited Catterline at the end of March, The Watchie was being used by local artist Mike Samson, busy preparing paintings for an exhibition in Aberdeen, and by members of a community arts group. Artist Stuart Buchanan who re-located from Glasgow to Catterline and to Eardley’s house at Number 18 two years ago has just begun a one year residency in The Watchie. Although not directly influenced by Eardley, it seems that a knowledge of her work and her evocation of these surroundings will impact on his painting. Certainly, it is difficult to avoid visualising her paintings while looking at this landscape, demonstrative perhaps, of her direct and experiential approach to her work. This approach – her constant observation and subsequent interpretation of the austerity and drama of the landscape, the muted colours of the north-east in her paintings is documented in photographs of Eardley with her easel set up on the shoreline.

For artists who come and work in The Watchie, many will find it is more than a space, a studio – with its outlook and position, it seems to both encompass and be integral to the surrounding landscape. For Eardley, to be part of this landscape and to be directly responding to it was fundamental to her work. This intimate involvement within the landscape produces the intensity and immediacy conveyed through her paintings, as if she was reducing as much as she could, the physical and emotional distance between artist and subject. Immersed in the elements she was recording, the paint itself is indicative of this engagement, both in the energy of the brushstrokes and for example, by the incorporation of sand and grasses in the paint.

Her painterly response and involvement in the community at Catterline have left lasting impressions which are not likely to diminish but to continue to feed imaginations and creative minds for many years to follow. Throughout Scotland in 2008, a touring exhibition Impressions of Catterline 08 will take place. Opening at Montrose Museum, it features work by eighteen artists, each responding to Catterline and its surroundings.

Text copyright, Scottish Art News 2008.