2009 —

Weaving Two Views: Victoria Crowe and Dovecot Studios

Weaving Two Views: Victoria Crowe and Dovecot Studios

Scottish Art News, Issue 11︎

︎PDF

![]()

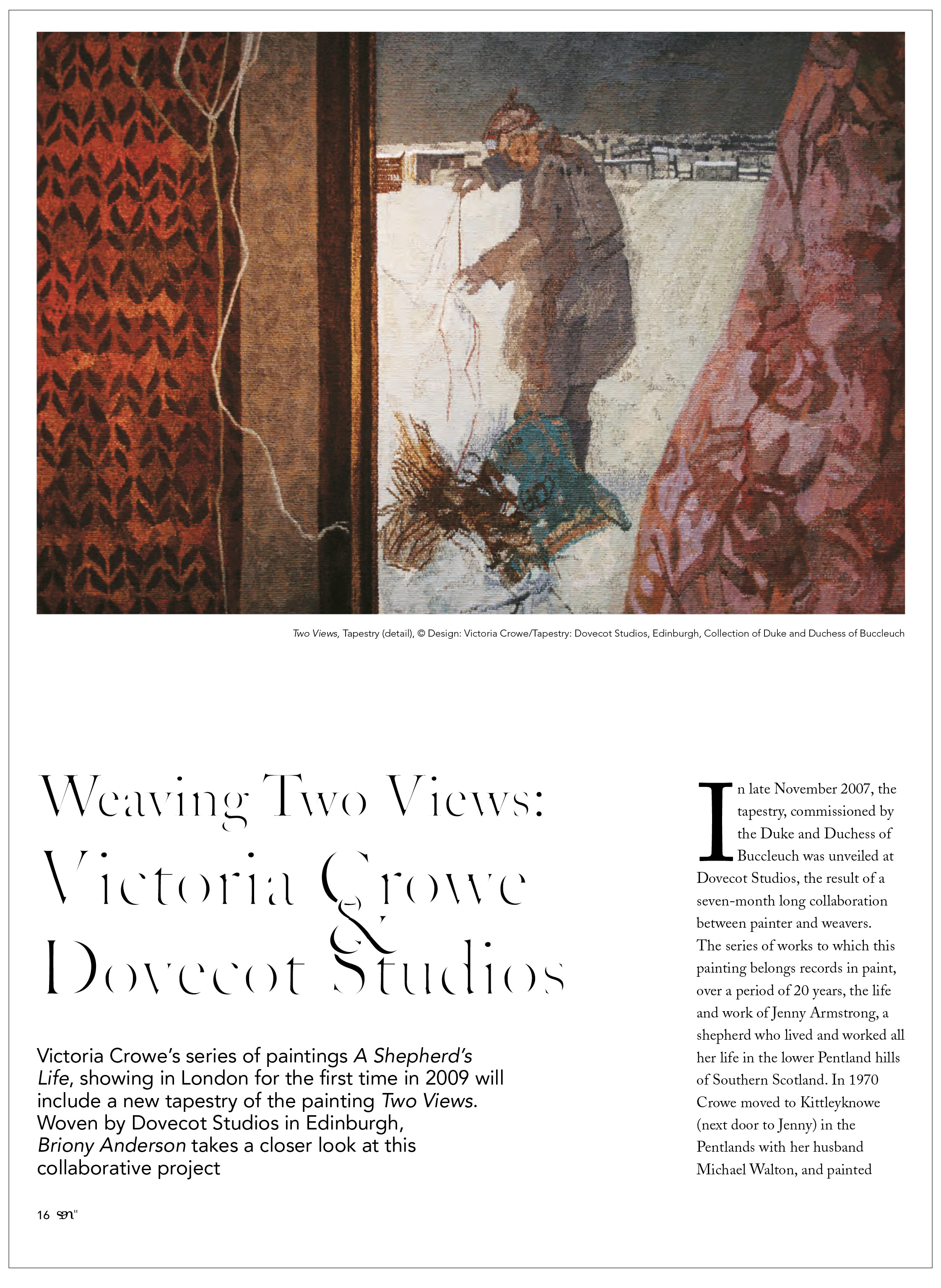

In late November 2007, a tapestry, commissioned by the Duke and Duchess of Buccleuch was unveiled at Dovecot Studios, the result of a seven-month long collaboration between painter and weavers. The series of works to which this painting belongs, records in paint, over a period of 20 years, the life and work of Jenny Armstrong, a shepherd who lived and worked all her life in the lower Pentland hills of Southern Scotland. In 1970 Crowe moved to Kittleyknowe (next door to Jenny) in the Pentlands with her husband Michael Walton, and painted Jenny both at home, within a domestic setting and at work in the landscape. While the works can be divided into ‘interior’ and ‘exterior’ paintings, Two Views (1980-81) perhaps more strongly than any other in the series, brings together both views: the interior of Jenny’s cottage and the winter landscape seen through the window, framing Jenny herself immersed in her work.

Within the painting Crowe has made a clear division between the interior and exterior – the warm, rich and homely shades of the patterned wallpaper and rose motif curtains and the colder, luminous hues of the snow- covered fields. But the baler twine pinned to the wall links the two spaces, marking Jenny’s presence and defining this as her home. Crowe has observed the two spaces together within a single frame – Jenny’s home life and professional life intertwined.

Both views are intimate. The private interior space and the glimpse of Jenny seen through the curtains, oblivious to being watched seem almost voyeuristic as the viewer looks out from within, just as Crowe had depicted her from the warm confines of Jenny’s home. This contrast between the security and warmth of her home and the cold, bleak outlook serves to emphasise the long, hard Scottish winter and human toil. The work had always to be carried out, regardless of the weather. Furthermore, the photograph of Jenny’s father hanging on the wall – springtime, lambing, bag, crook and dog – contrasts the reality of Jenny and her work against the more romantic, idealised view of the shepherd.

Crowe has spoken of her long-term ambition of creating a tapestry from this series and upon confirmation of the exhibition at The Fleming Collection, saw the gallery and its dark mahogany wall as the ideal context. In 2007 the opportunity arose to fulfil this ambition with a commission from a longtime collector of Crowe’s work, The Duke of Buccleuch. On visiting Crowe’s studio to select the work from which the tapestry would be made, it was the subject matter of Two Views: the home, its environs, the family and a sense of a continuum in time and tradition, which led to this final choice, and a long and intensive collaboration with weavers Douglas Grierson, Naomi Robertson and David Cochrane, at Dovecot. Interestingly, Two Views was also the work chosen by weaver Douglas Grierson who recognised that the warm, rich tones used in the painting would translate well into a tapestry. The work selected, the project developed apace with Crowe’s involvement fundamental to the completed work.

The weavers were invited to Kittleyknowe to see the paintings (and subsequently had Two Views with them throughout the weaving process) to gain a sense of the landscape, the quality of light, and in particular, to see the moorland and reed beds under snow. Wool was collected from the surrounding fields and was subsequently spun into strands. With this wool one of the weavers, David Cochrane began a small sample of another of Crowe’s paintings from ‘A Shepherd’s Life’, Large Tree Group (1975) which was displayed alongside Two Views (painting and tapestry) at Dovecot Studios after the project was complete. Although not used to weave Two Views, the inherent qualities of natural, local, undyed wool – for example, the colours never fade, is something Crowe is keen to exploit in a future project.

Influenced by William Morris, the fourth Marquess of Bute established the Dovecot Studios at Corstorphine in Edinburgh in 1912 and it was from Morris’ workshop at Merton Abbey near London that the first two master weavers came.1 Morris attacked the separation of fine art from craft and the artist from the artisan which had taken place during the 18th century when the concept of art was

spilt apart, generating the new category fine arts (poetry, painting, sculpture, architecture, music) as opposed to crafts and popular arts (shoemaking, embroidery, popular songs, etc).2 In The Invention of Art, Larry Shiner credits Morris, along with Ruskin, as posing the most thoroughly worked out challenge to the fine art-versus- craft split with their ideas finding institutional embodiment in the Arts and Crafts movement in the last decades of the 19th century – this historical separation ‘ruinous’ to both.3 Albeit full of inconsistency and failing to match its ideals, this attitude to the dichotomies of the modern fine art system, ‘a modern invention’, and demotion of the crafts and popular arts, fed directly into Dovecot and there evolved a firm belief in the co-operation between artist and craftsman.4

Historically, the role of artist as designer of tapestry without experience or skills and practice of weaving has only existed over the last 450 years and for the artist, this new territory opens up new ways of approach. Crowe’s involvement in the transposition of the painting into a tapestry was most marked at the beginning of the project. Once the painting (design) was selected, a cartoon (full-scale linear design for the tapestry) was made. Measuring four feet by eight feet – twice the size of the original painting – the cartoon was then ‘inked-on’ to the warp. Crowe had made certain alterations to the original composition, such as lowering the horizon to bring Jenny’s hand in line with the houses. The work was not copied (‘painting by numbers’) but translated and interpreted – a much more subtle and complex process during which new and unexpected possibilites for the work can arise. The quality of line is reassessed and the range of colour expanded, for example, the colour of the curtains enlivened. Woven in 1912 Dovecot stock wool, the weft (horizontal threads woven in and out of the warp) was mixed for each area of colour as a painter mixes paint on a palette, demonstrating not only a flexibility in the handling of materials but in the weaving itself. Depending on the composition of the tapestry, it can be woven upright or on its side, which dictates how many weavers can work on it at any one time. Two Views was woven on its side allowing for two weavers to work alongside.

Crowe has remarked on the shift in her understanding of the work that took place as the tapestry was unveiled during the ‘Cutting off Ceremony’. As the tension on the warp threads has to remain constant throughout the weaving and the structural integrity of the fabric demands that no one part be allowed to develop more than a few inches ahead of the rest, only a small section was visible at any one time. For a painter, used to working freely across a whole surface, seeing the work in its entirety for the very first time in such a way was a novel experience. As a tapestry is cut off, the tension goes and the tapestry sags. This transition from a solid, unmoving surface to something which could be unfurled, rolled up and held under one’s arm, and the tapestry’s absorption of light rather tha its reflection, brought about a significant shift in her perception. She has likened the unveiling to her experience of seeing her work removed from the studio and reconfigured in a new context in A Shepherd’s Life, first shown at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery in 2000.

In explaining the process of transposition from painting to tapestry, Archie Brennan who became Director of the Dovecot Studios in 1963 and who was instrumental in Dovecot’s development and progress, has emphasised the importance of collaboration.5 For Brennan, the principal tenet is that a tapestry must be an ‘extension’ of the work; it should not be some variation on the original, but have an identity of its own, which is the ‘heart of the approach’.6 There needs to be an informed understanding of the original work, a reciprocal respect between painter and weaver and a sensitivity to each medium where the limits and potential of each are recognised. He explains that there is no ‘system’ of interpretatio or transposition, the success of a tapestry never guaranteed.

For Dovecot and Crowe, this collaboration does not challenge the ‘holy status’ of the individual or diminish the individual authority over that individual’s particular part of the project; these collaborator are individuals involved in a shared project, each benefiting from the other’s specialist knowledge. However, there is a level of engagement within this collaboration that departs from a view held of contemporary art that a certain degree of detachment of the artist has symptomatically led to ‘the idea of an externalised system or agent that makes the work (on the artist’s behalf ) becoming normalised within contemporary art production’.7 With artists utilising others to make the work on the artist’s behalf, ‘the conversation of the collaboration can easily become the object that believes, in place of the unbelieving individual.’ 8

The issues of underlying polarities of the fine art system questioned by Morris and Co. were addressed by Dovecot Studios, allowing for an engaged form of collaboration – one that moved across divisions, doing much to raise its profile. The ability of weavers to translate the work of artists in such a way that allows for creativity in both parties, to ultimately find the best solution and to build a relationship of mutual confidence is one which both Crowe and Dovecot feel was achieved in this commission.

Text copyright, Scottish Art News 2009.

***

1 Maureen Hodge, ‘A History of the Dovecot Studios’ in Master Weavers: Tapestry from the Dovecot Studios 1912-1980, Canongate, Edinburgh, 1980

2 After the 19th century usage dropped the adjective ‘fine’, Larry Shiner, The Invention of Art: A Cultural History, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2001

3 Ibid., p.138

4 Ibid.

5 Archie Brennan, ‘The Transposition of a Painting into a Tapestry’ in Master Weavers: Tapestry from the Dovecot Studios 1912-1980, Canongate, Edinburgh, 1980, pp.33-6

6 Ibid.

7 Dave Beech, Mark Hutchinson and John Timberlake, Analysis (Transmission: the Rules of Engagement), Artwords Press, p.12

8 Ibid.

In late November 2007, a tapestry, commissioned by the Duke and Duchess of Buccleuch was unveiled at Dovecot Studios, the result of a seven-month long collaboration between painter and weavers. The series of works to which this painting belongs, records in paint, over a period of 20 years, the life and work of Jenny Armstrong, a shepherd who lived and worked all her life in the lower Pentland hills of Southern Scotland. In 1970 Crowe moved to Kittleyknowe (next door to Jenny) in the Pentlands with her husband Michael Walton, and painted Jenny both at home, within a domestic setting and at work in the landscape. While the works can be divided into ‘interior’ and ‘exterior’ paintings, Two Views (1980-81) perhaps more strongly than any other in the series, brings together both views: the interior of Jenny’s cottage and the winter landscape seen through the window, framing Jenny herself immersed in her work.

Within the painting Crowe has made a clear division between the interior and exterior – the warm, rich and homely shades of the patterned wallpaper and rose motif curtains and the colder, luminous hues of the snow- covered fields. But the baler twine pinned to the wall links the two spaces, marking Jenny’s presence and defining this as her home. Crowe has observed the two spaces together within a single frame – Jenny’s home life and professional life intertwined.

Both views are intimate. The private interior space and the glimpse of Jenny seen through the curtains, oblivious to being watched seem almost voyeuristic as the viewer looks out from within, just as Crowe had depicted her from the warm confines of Jenny’s home. This contrast between the security and warmth of her home and the cold, bleak outlook serves to emphasise the long, hard Scottish winter and human toil. The work had always to be carried out, regardless of the weather. Furthermore, the photograph of Jenny’s father hanging on the wall – springtime, lambing, bag, crook and dog – contrasts the reality of Jenny and her work against the more romantic, idealised view of the shepherd.

Crowe has spoken of her long-term ambition of creating a tapestry from this series and upon confirmation of the exhibition at The Fleming Collection, saw the gallery and its dark mahogany wall as the ideal context. In 2007 the opportunity arose to fulfil this ambition with a commission from a longtime collector of Crowe’s work, The Duke of Buccleuch. On visiting Crowe’s studio to select the work from which the tapestry would be made, it was the subject matter of Two Views: the home, its environs, the family and a sense of a continuum in time and tradition, which led to this final choice, and a long and intensive collaboration with weavers Douglas Grierson, Naomi Robertson and David Cochrane, at Dovecot. Interestingly, Two Views was also the work chosen by weaver Douglas Grierson who recognised that the warm, rich tones used in the painting would translate well into a tapestry. The work selected, the project developed apace with Crowe’s involvement fundamental to the completed work.

The weavers were invited to Kittleyknowe to see the paintings (and subsequently had Two Views with them throughout the weaving process) to gain a sense of the landscape, the quality of light, and in particular, to see the moorland and reed beds under snow. Wool was collected from the surrounding fields and was subsequently spun into strands. With this wool one of the weavers, David Cochrane began a small sample of another of Crowe’s paintings from ‘A Shepherd’s Life’, Large Tree Group (1975) which was displayed alongside Two Views (painting and tapestry) at Dovecot Studios after the project was complete. Although not used to weave Two Views, the inherent qualities of natural, local, undyed wool – for example, the colours never fade, is something Crowe is keen to exploit in a future project.

Influenced by William Morris, the fourth Marquess of Bute established the Dovecot Studios at Corstorphine in Edinburgh in 1912 and it was from Morris’ workshop at Merton Abbey near London that the first two master weavers came.1 Morris attacked the separation of fine art from craft and the artist from the artisan which had taken place during the 18th century when the concept of art was

spilt apart, generating the new category fine arts (poetry, painting, sculpture, architecture, music) as opposed to crafts and popular arts (shoemaking, embroidery, popular songs, etc).2 In The Invention of Art, Larry Shiner credits Morris, along with Ruskin, as posing the most thoroughly worked out challenge to the fine art-versus- craft split with their ideas finding institutional embodiment in the Arts and Crafts movement in the last decades of the 19th century – this historical separation ‘ruinous’ to both.3 Albeit full of inconsistency and failing to match its ideals, this attitude to the dichotomies of the modern fine art system, ‘a modern invention’, and demotion of the crafts and popular arts, fed directly into Dovecot and there evolved a firm belief in the co-operation between artist and craftsman.4

Historically, the role of artist as designer of tapestry without experience or skills and practice of weaving has only existed over the last 450 years and for the artist, this new territory opens up new ways of approach. Crowe’s involvement in the transposition of the painting into a tapestry was most marked at the beginning of the project. Once the painting (design) was selected, a cartoon (full-scale linear design for the tapestry) was made. Measuring four feet by eight feet – twice the size of the original painting – the cartoon was then ‘inked-on’ to the warp. Crowe had made certain alterations to the original composition, such as lowering the horizon to bring Jenny’s hand in line with the houses. The work was not copied (‘painting by numbers’) but translated and interpreted – a much more subtle and complex process during which new and unexpected possibilites for the work can arise. The quality of line is reassessed and the range of colour expanded, for example, the colour of the curtains enlivened. Woven in 1912 Dovecot stock wool, the weft (horizontal threads woven in and out of the warp) was mixed for each area of colour as a painter mixes paint on a palette, demonstrating not only a flexibility in the handling of materials but in the weaving itself. Depending on the composition of the tapestry, it can be woven upright or on its side, which dictates how many weavers can work on it at any one time. Two Views was woven on its side allowing for two weavers to work alongside.

Crowe has remarked on the shift in her understanding of the work that took place as the tapestry was unveiled during the ‘Cutting off Ceremony’. As the tension on the warp threads has to remain constant throughout the weaving and the structural integrity of the fabric demands that no one part be allowed to develop more than a few inches ahead of the rest, only a small section was visible at any one time. For a painter, used to working freely across a whole surface, seeing the work in its entirety for the very first time in such a way was a novel experience. As a tapestry is cut off, the tension goes and the tapestry sags. This transition from a solid, unmoving surface to something which could be unfurled, rolled up and held under one’s arm, and the tapestry’s absorption of light rather tha its reflection, brought about a significant shift in her perception. She has likened the unveiling to her experience of seeing her work removed from the studio and reconfigured in a new context in A Shepherd’s Life, first shown at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery in 2000.

In explaining the process of transposition from painting to tapestry, Archie Brennan who became Director of the Dovecot Studios in 1963 and who was instrumental in Dovecot’s development and progress, has emphasised the importance of collaboration.5 For Brennan, the principal tenet is that a tapestry must be an ‘extension’ of the work; it should not be some variation on the original, but have an identity of its own, which is the ‘heart of the approach’.6 There needs to be an informed understanding of the original work, a reciprocal respect between painter and weaver and a sensitivity to each medium where the limits and potential of each are recognised. He explains that there is no ‘system’ of interpretatio or transposition, the success of a tapestry never guaranteed.

For Dovecot and Crowe, this collaboration does not challenge the ‘holy status’ of the individual or diminish the individual authority over that individual’s particular part of the project; these collaborator are individuals involved in a shared project, each benefiting from the other’s specialist knowledge. However, there is a level of engagement within this collaboration that departs from a view held of contemporary art that a certain degree of detachment of the artist has symptomatically led to ‘the idea of an externalised system or agent that makes the work (on the artist’s behalf ) becoming normalised within contemporary art production’.7 With artists utilising others to make the work on the artist’s behalf, ‘the conversation of the collaboration can easily become the object that believes, in place of the unbelieving individual.’ 8

The issues of underlying polarities of the fine art system questioned by Morris and Co. were addressed by Dovecot Studios, allowing for an engaged form of collaboration – one that moved across divisions, doing much to raise its profile. The ability of weavers to translate the work of artists in such a way that allows for creativity in both parties, to ultimately find the best solution and to build a relationship of mutual confidence is one which both Crowe and Dovecot feel was achieved in this commission.

Text copyright, Scottish Art News 2009.

***

1 Maureen Hodge, ‘A History of the Dovecot Studios’ in Master Weavers: Tapestry from the Dovecot Studios 1912-1980, Canongate, Edinburgh, 1980

2 After the 19th century usage dropped the adjective ‘fine’, Larry Shiner, The Invention of Art: A Cultural History, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2001

3 Ibid., p.138

4 Ibid.

5 Archie Brennan, ‘The Transposition of a Painting into a Tapestry’ in Master Weavers: Tapestry from the Dovecot Studios 1912-1980, Canongate, Edinburgh, 1980, pp.33-6

6 Ibid.

7 Dave Beech, Mark Hutchinson and John Timberlake, Analysis (Transmission: the Rules of Engagement), Artwords Press, p.12

8 Ibid.