2013 —

Lines Lost

Lines Lost

Scottish Art News, Issue 20︎

︎PDF

![]()

2013 marks 50 years since the British Railways Board’s publication of Dr Richard Beeching’s ‘The Reshaping of British Railways’ report, which recommended the closure of one third of Britain’s 7,000 railway stations along with 5,000 miles of the 18,000-mile rail network. The north of Scotland was particularly affected by the line closures which had a deep impact on those living and working along its routes. Author and railway expert David Spaven believes that three of the 10 worst closures were in Scotland, with the 43-mile Aberdeen – Fraserburgh route among these. By the early 1970s the transition from rail to road was complete for many living in the north of Scotland and this historical shift is to form the basis of Lines Lost, a project by Glasgow-based artist Stuart McAdam. Commissioned by Deveron Arts, a contemporary arts organisation in Huntly, Aberdeenshire, the core of the project is McAdam’s proposal to walk the area’s dismantled railway lines from which a series of talks, events and artworks will emerge.

The recent renewed debates surrounding the Beeching cuts brings into sharp focus the idea of journeying and in particular the idea of ‘slow travel’, a concept which Deveron Arts has been investigating through a programme of events, residencies and projects within the local community. It is an area of specific personal interest for both McAdam and Director of Deveron Arts, Claudia Zeiske. For Zeiske, the journey itself can become the destination ‘In a fast moving world, where arriving has become more important than the journey – we miss so much’. (She recently undertook a five-day train journey to Lapland.) It isn’t, however, just this corner of the north-east of Scotland which is exploring slow travel. McAdam points out that the city of Perth has been granted ‘Cittaslow’ status as part of a global network of towns trying to improve the quality of life for its inhabitants. Cittaslow’s list of aims includes increasing alternative mobility such as walking and cycling, with places throughout the town for people to sit down and rest. But within the context of Lines Lost there is a paradox. Slow travel was forced upon many communities. Far longer and less pleasant journeys by road became the only means by which to travel from the towns, giving ‘slow travel’ a very different meaning for those from whom the choice was removed.

McAdam will spend three months in Huntly although he has already been working with ideas for the project for many months. His work has been increasingly focused on ideas surrounding slow travel and he has been countering the rapid speed and fragmented nature of our journeys through a series of projects which allow him ‘to feel every bump in the road’. His previous projects centred on the journey have mostly involved the artist himself undertaking long journeys by various means. In A Proposal (2010) the artist cycled from his home in Scotland to Utrecht in the Netherlands where he used to live. In Union (2012) he constructed a wooden canoe with artist Neil Scott (who he has often collaborated with) using it to travel along Scotland’s internal waterways. In the same year he undertook a cycle trip through Belgium and France to Switzerland following the line of the western front trenches of the First World War. For Lines Lost the artist has proposed a journey by foot along the once well-travelled dismantled railway lines, now faint traces on the land – what McAdam has called ‘ ready-made lines in the landscape’.

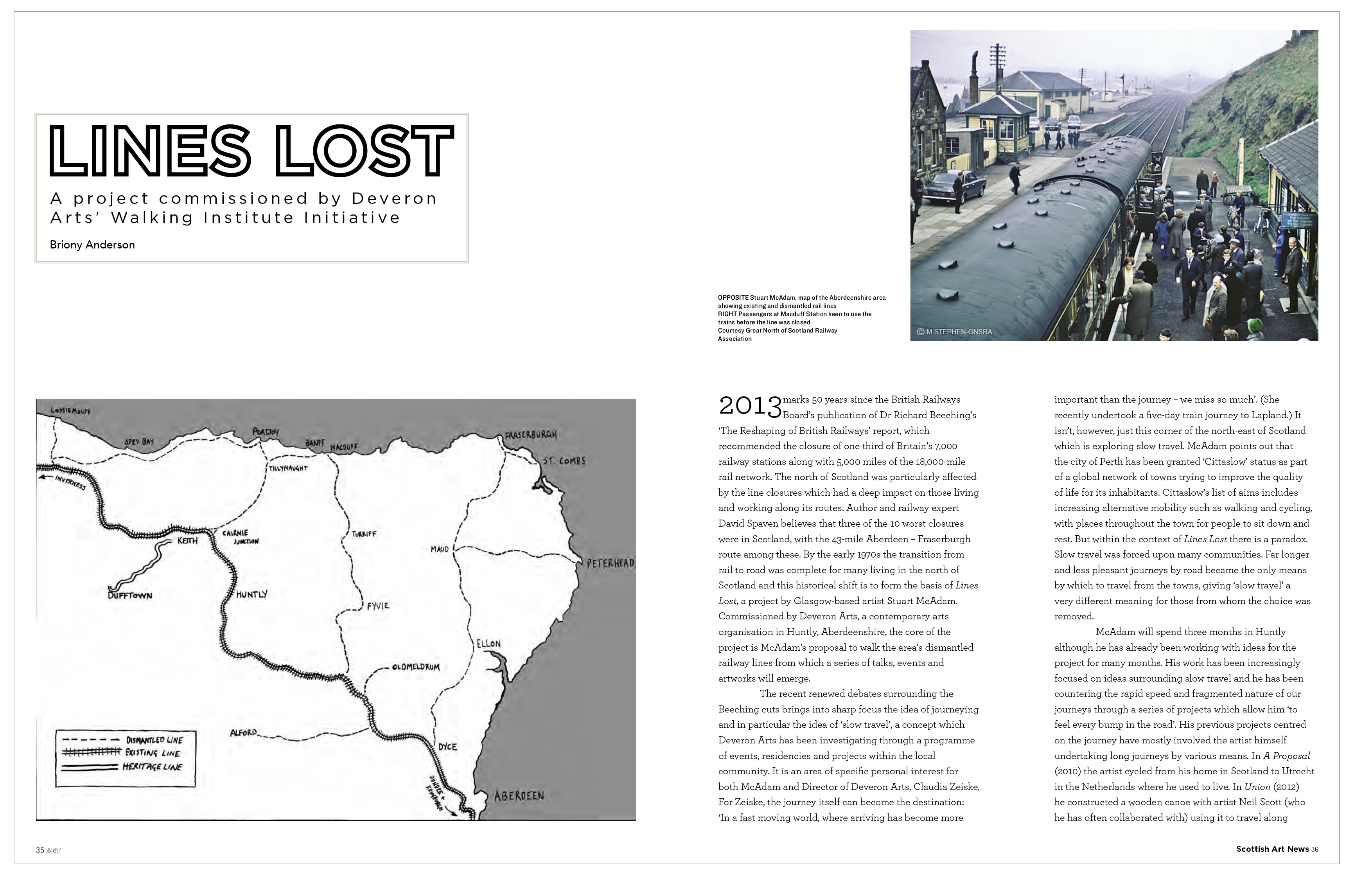

McAdam has been slowly making his way through the Beeching Report, a dense governmental paper, trying to gain an understanding of the context in which the decisions were made. But studying maps has proved much more fruitful, particularly comparing maps from the 1920s and ‘30s with contemporary maps. For an artist interested in slow travel, which allows him to note changes and details along the routes he walks, it isn’t surprising that he is happier studying maps, identifying the changes on paper. In this sense the map becomes for the artist what a pencil and sketchbook are for a landscape painter. The nineteenth- century Bradshaw Guides have also proved a useful source of information about the towns and their inhabitants. These historical guides have perhaps more of a focus on the journey, and the experience of journeying itself.

Although keen to remain impartial – his work is not overtly political in its intention – it would be impossible for him to consider the work without recognising the controversy and impact of the cuts. During the protests against the closures, local people in the Borders town of Hawick sent a replica coffin on the last train out of town, addressed to the transport minister. (With the closure of the Waverley Route, Hawick was nearly 50 miles from the nearest railway station.) This particular act of protest has stuck with the artist. Throughout the project he will invite various people to join him on the walks, from local people to those with specialist knowledge, possibly also local politicians and other artists. The project traverses a terrain which is both poetic (the artistic gesture) and political (the context). The work of Belgian artist Francis Alÿs is of particular interest to McAdam. In 1995 Alÿs walked with a leaking can of blue paint throughout São Paulo, ‘painting’ a line, a poetic gesture. In 2004 he re-enacted this but followed a portion of the ‘Green Line’ that runs through a municipality of Jerusalem (The Green Line, 2004).

Rather than being restricted to any particular medium, McAdam’s work evolves in relation to the nature of the project, producing various outcomes (drawings, collage, three-dimensional objects, film, performance, writing), although the outcomes often take the form of mapping and drawing. He traces his journeys both by hand onto the maps themselves and by GPS, which enables him to collect data quickly. The dismantled railway lines he will walk are represented on the maps as dashed lines. On his maps he will trace his journey with pencil, the lines once again becoming complete.

There have been a number of recent exhibitions (for example Walk On: 40 years of art walking from Richard Long to Janet Cardiff, touring, 2013) and publications, which have been exploring the idea of walking as art. A recent publication by David Evans, The Art of Walking: a field guide (Blackdog Publishing, 2012), begins with a proposal from the artist Peter Liversidge: ‘I propose that you put down this book and go outside’. There is a loveliness in the simplicity of this proposal while it also speaks of the increasing number of artists making contemporary artwork that deals with walking, privileging open landscape over the studio. In the early decades of the twentieth century, the representation of the modern artist as wanderer, for example in Gustave Courbet’s Bonjour Monsieur Courbet (1854), had shifted to its practice as the avant-garde sought to merge art and life. Walking as a creative activity has nonetheless, in many cases, come to be represented by objects displayed in museums.

Currently there seems to be an increasing interest in art that involves walking, echoed by a resurgence of popular interest in nature and landscape writing. It would seem as if the further nature feels from us, distanced more and more from how we live and work, the more demand there is for work which re-engages with landscape, memory and the environment. Perhaps, in relation to the premise of Lines Lost, German writer and academic WG Sebald is relevant. In The Rings of Saturn, Sebald walks in East Anglia recording his journey which becomes the catalyst for evocations of people and cultures past and present. There is a refusal to allow the past to fade from memory.

The north-east landscape McAdam will walk into and across, has been marked by the building, running and closure of the railway lines. It is a landscape altered by human presence – artifice in the moment of its beholding long before it becomes a subject of representation. Landscape ‘naturalises a cultural and social construction, representing an artificial world as it were simply given and inevitable’ (WJT Mitchell, Landscape and Power, The University of Chicago Press, 1994, p.2). Where much artistic representation of landscape tends to obliterate history, McAdam instead looks to reawaken a consciousness of history through time spent walking, observing and engaging with the landscape. He is keen to make people aware of what happened 50 years ago. As many of the lines are now largely overgrown, reclaimed by trees, it is easy to be unaware that a line ever existed.

With McAdam’s first walk involving trudging through overgrowth at an average speed of 1 mph, this route will prove tougher than the cycle paths of his childhood along disused lines in Renfrewshire. Although many railway tracks have become walking paths (in the UK there are more than 1,500 miles of cycle pathway which have been built on old rail track), because Huntly sits outside the boundary of the Cairngorms National Park it has missed out on funding which possibly could have seen the disused lines being repurposed. This fact may lead to another proposal, a proposal for a new use for the lines.

McAdam comes to the north-east as an outsider, as a tourist perhaps, as someone who did not witness the impact of the cuts. But for him this is less a negative aspect or hindrance, but rather the opportunity to engage much more fully – with all his senses – with the area and local people. It can often be the case that one engages less fully with what’s familiar, what’s on the doorstep, in contrast to an unfamiliar environment. Finding his way along new lines in a new place allows for him a heightened consciousness and interest. He points to the fact that Beeching himself was very much an ‘outsider’ when he wrote his report, unaware of the patterns of life of the local inhabitants. The academic and writer Robert Macfarlane has talked about walking as a way of ‘special seeing’, a means to explore ‘the ongoing puzzle of how the landscape shapes us’.

The project has immediate strength from the outset. As a proposal it is rich in subject matter and the specificities of the outcomes of the project will emerge as the project progresses. For now, McAdam isn’t sure how the outcomes of the project will manifest themselves, but he is relatively certain that any outcomes, whether in sculptural, pictorial or written form, are unlikely to be displayed in a gallery setting and are far more likely to be found in a public space like a train station, or within the landscape itself. It isn’t necessary to define his practice through categorisation. His work involves journeying, it’s socially engaged, performative, fine-art based and although his work is interested in boundaries and how they become imprinted on the land, within his practice, boundaries are irrelevant.

During his undergraduate studies at Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art, his work involved walking – walking the city of Dundee while drawing on the ideas of Guy Debord and the Situationist International (1957–72) and their engagement with the city in alternative, personal and creative ways, defying the commercial logic of the modern city. The works McAdam made as an outcome of these walks were often linear, whether lines on maps or line drawings. But recently he has become more interested in tone and shading and colour. Perhaps this project echoes this different way of seeing; the lines are but one aspect – the means for him to walk and explore – but it’s the spaces in between, the villages, towns and people, who made, used and lost the lines, for whom you suspect this project will have most resonance. In The Waves by Virginia Woolf, one of the book’s characters says that ‘as we walk, time comes back’. This thought is certainly apt for an artist’s journey without a clear destination. We can’t walk back into a previous time but the project doesn’t allow us to forget. By walking the lines and mapping the walks, he is also in some way mapping the lives of those living there, seeking an understanding of ourselves in relation to the landscape we travel through.

As part of the Edinburgh Art Festival Stuart McAdam and Director of Deveron Arts, Claudia Zeiske, will lead a discussion about the relationship between art, walking and transport in Scotland, after a walk around Edinburgh.

Lines Lost Discussion, 1 August 2013, 4pm

Royal Scottish Academy, The Mound, Edinburgh

www.edinburghartfestival.com/events www.deveron-arts.com

Text copyright, Scottish Art News 2013.

2013 marks 50 years since the British Railways Board’s publication of Dr Richard Beeching’s ‘The Reshaping of British Railways’ report, which recommended the closure of one third of Britain’s 7,000 railway stations along with 5,000 miles of the 18,000-mile rail network. The north of Scotland was particularly affected by the line closures which had a deep impact on those living and working along its routes. Author and railway expert David Spaven believes that three of the 10 worst closures were in Scotland, with the 43-mile Aberdeen – Fraserburgh route among these. By the early 1970s the transition from rail to road was complete for many living in the north of Scotland and this historical shift is to form the basis of Lines Lost, a project by Glasgow-based artist Stuart McAdam. Commissioned by Deveron Arts, a contemporary arts organisation in Huntly, Aberdeenshire, the core of the project is McAdam’s proposal to walk the area’s dismantled railway lines from which a series of talks, events and artworks will emerge.

The recent renewed debates surrounding the Beeching cuts brings into sharp focus the idea of journeying and in particular the idea of ‘slow travel’, a concept which Deveron Arts has been investigating through a programme of events, residencies and projects within the local community. It is an area of specific personal interest for both McAdam and Director of Deveron Arts, Claudia Zeiske. For Zeiske, the journey itself can become the destination ‘In a fast moving world, where arriving has become more important than the journey – we miss so much’. (She recently undertook a five-day train journey to Lapland.) It isn’t, however, just this corner of the north-east of Scotland which is exploring slow travel. McAdam points out that the city of Perth has been granted ‘Cittaslow’ status as part of a global network of towns trying to improve the quality of life for its inhabitants. Cittaslow’s list of aims includes increasing alternative mobility such as walking and cycling, with places throughout the town for people to sit down and rest. But within the context of Lines Lost there is a paradox. Slow travel was forced upon many communities. Far longer and less pleasant journeys by road became the only means by which to travel from the towns, giving ‘slow travel’ a very different meaning for those from whom the choice was removed.

McAdam will spend three months in Huntly although he has already been working with ideas for the project for many months. His work has been increasingly focused on ideas surrounding slow travel and he has been countering the rapid speed and fragmented nature of our journeys through a series of projects which allow him ‘to feel every bump in the road’. His previous projects centred on the journey have mostly involved the artist himself undertaking long journeys by various means. In A Proposal (2010) the artist cycled from his home in Scotland to Utrecht in the Netherlands where he used to live. In Union (2012) he constructed a wooden canoe with artist Neil Scott (who he has often collaborated with) using it to travel along Scotland’s internal waterways. In the same year he undertook a cycle trip through Belgium and France to Switzerland following the line of the western front trenches of the First World War. For Lines Lost the artist has proposed a journey by foot along the once well-travelled dismantled railway lines, now faint traces on the land – what McAdam has called ‘ ready-made lines in the landscape’.

McAdam has been slowly making his way through the Beeching Report, a dense governmental paper, trying to gain an understanding of the context in which the decisions were made. But studying maps has proved much more fruitful, particularly comparing maps from the 1920s and ‘30s with contemporary maps. For an artist interested in slow travel, which allows him to note changes and details along the routes he walks, it isn’t surprising that he is happier studying maps, identifying the changes on paper. In this sense the map becomes for the artist what a pencil and sketchbook are for a landscape painter. The nineteenth- century Bradshaw Guides have also proved a useful source of information about the towns and their inhabitants. These historical guides have perhaps more of a focus on the journey, and the experience of journeying itself.

Although keen to remain impartial – his work is not overtly political in its intention – it would be impossible for him to consider the work without recognising the controversy and impact of the cuts. During the protests against the closures, local people in the Borders town of Hawick sent a replica coffin on the last train out of town, addressed to the transport minister. (With the closure of the Waverley Route, Hawick was nearly 50 miles from the nearest railway station.) This particular act of protest has stuck with the artist. Throughout the project he will invite various people to join him on the walks, from local people to those with specialist knowledge, possibly also local politicians and other artists. The project traverses a terrain which is both poetic (the artistic gesture) and political (the context). The work of Belgian artist Francis Alÿs is of particular interest to McAdam. In 1995 Alÿs walked with a leaking can of blue paint throughout São Paulo, ‘painting’ a line, a poetic gesture. In 2004 he re-enacted this but followed a portion of the ‘Green Line’ that runs through a municipality of Jerusalem (The Green Line, 2004).

Rather than being restricted to any particular medium, McAdam’s work evolves in relation to the nature of the project, producing various outcomes (drawings, collage, three-dimensional objects, film, performance, writing), although the outcomes often take the form of mapping and drawing. He traces his journeys both by hand onto the maps themselves and by GPS, which enables him to collect data quickly. The dismantled railway lines he will walk are represented on the maps as dashed lines. On his maps he will trace his journey with pencil, the lines once again becoming complete.

There have been a number of recent exhibitions (for example Walk On: 40 years of art walking from Richard Long to Janet Cardiff, touring, 2013) and publications, which have been exploring the idea of walking as art. A recent publication by David Evans, The Art of Walking: a field guide (Blackdog Publishing, 2012), begins with a proposal from the artist Peter Liversidge: ‘I propose that you put down this book and go outside’. There is a loveliness in the simplicity of this proposal while it also speaks of the increasing number of artists making contemporary artwork that deals with walking, privileging open landscape over the studio. In the early decades of the twentieth century, the representation of the modern artist as wanderer, for example in Gustave Courbet’s Bonjour Monsieur Courbet (1854), had shifted to its practice as the avant-garde sought to merge art and life. Walking as a creative activity has nonetheless, in many cases, come to be represented by objects displayed in museums.

Currently there seems to be an increasing interest in art that involves walking, echoed by a resurgence of popular interest in nature and landscape writing. It would seem as if the further nature feels from us, distanced more and more from how we live and work, the more demand there is for work which re-engages with landscape, memory and the environment. Perhaps, in relation to the premise of Lines Lost, German writer and academic WG Sebald is relevant. In The Rings of Saturn, Sebald walks in East Anglia recording his journey which becomes the catalyst for evocations of people and cultures past and present. There is a refusal to allow the past to fade from memory.

The north-east landscape McAdam will walk into and across, has been marked by the building, running and closure of the railway lines. It is a landscape altered by human presence – artifice in the moment of its beholding long before it becomes a subject of representation. Landscape ‘naturalises a cultural and social construction, representing an artificial world as it were simply given and inevitable’ (WJT Mitchell, Landscape and Power, The University of Chicago Press, 1994, p.2). Where much artistic representation of landscape tends to obliterate history, McAdam instead looks to reawaken a consciousness of history through time spent walking, observing and engaging with the landscape. He is keen to make people aware of what happened 50 years ago. As many of the lines are now largely overgrown, reclaimed by trees, it is easy to be unaware that a line ever existed.

With McAdam’s first walk involving trudging through overgrowth at an average speed of 1 mph, this route will prove tougher than the cycle paths of his childhood along disused lines in Renfrewshire. Although many railway tracks have become walking paths (in the UK there are more than 1,500 miles of cycle pathway which have been built on old rail track), because Huntly sits outside the boundary of the Cairngorms National Park it has missed out on funding which possibly could have seen the disused lines being repurposed. This fact may lead to another proposal, a proposal for a new use for the lines.

McAdam comes to the north-east as an outsider, as a tourist perhaps, as someone who did not witness the impact of the cuts. But for him this is less a negative aspect or hindrance, but rather the opportunity to engage much more fully – with all his senses – with the area and local people. It can often be the case that one engages less fully with what’s familiar, what’s on the doorstep, in contrast to an unfamiliar environment. Finding his way along new lines in a new place allows for him a heightened consciousness and interest. He points to the fact that Beeching himself was very much an ‘outsider’ when he wrote his report, unaware of the patterns of life of the local inhabitants. The academic and writer Robert Macfarlane has talked about walking as a way of ‘special seeing’, a means to explore ‘the ongoing puzzle of how the landscape shapes us’.

The project has immediate strength from the outset. As a proposal it is rich in subject matter and the specificities of the outcomes of the project will emerge as the project progresses. For now, McAdam isn’t sure how the outcomes of the project will manifest themselves, but he is relatively certain that any outcomes, whether in sculptural, pictorial or written form, are unlikely to be displayed in a gallery setting and are far more likely to be found in a public space like a train station, or within the landscape itself. It isn’t necessary to define his practice through categorisation. His work involves journeying, it’s socially engaged, performative, fine-art based and although his work is interested in boundaries and how they become imprinted on the land, within his practice, boundaries are irrelevant.

During his undergraduate studies at Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art, his work involved walking – walking the city of Dundee while drawing on the ideas of Guy Debord and the Situationist International (1957–72) and their engagement with the city in alternative, personal and creative ways, defying the commercial logic of the modern city. The works McAdam made as an outcome of these walks were often linear, whether lines on maps or line drawings. But recently he has become more interested in tone and shading and colour. Perhaps this project echoes this different way of seeing; the lines are but one aspect – the means for him to walk and explore – but it’s the spaces in between, the villages, towns and people, who made, used and lost the lines, for whom you suspect this project will have most resonance. In The Waves by Virginia Woolf, one of the book’s characters says that ‘as we walk, time comes back’. This thought is certainly apt for an artist’s journey without a clear destination. We can’t walk back into a previous time but the project doesn’t allow us to forget. By walking the lines and mapping the walks, he is also in some way mapping the lives of those living there, seeking an understanding of ourselves in relation to the landscape we travel through.

As part of the Edinburgh Art Festival Stuart McAdam and Director of Deveron Arts, Claudia Zeiske, will lead a discussion about the relationship between art, walking and transport in Scotland, after a walk around Edinburgh.

Lines Lost Discussion, 1 August 2013, 4pm

Royal Scottish Academy, The Mound, Edinburgh

www.edinburghartfestival.com/events www.deveron-arts.com

Text copyright, Scottish Art News 2013.